The story behind the British war graves in Halle (NL)

The WellingtonT2559

This is an edited version of an article originally published in March 2007.

For more information please contact:

Bert Schieven, Dit e-mailadres wordt beveiligd tegen spambots. JavaScript dient ingeschakeld te zijn om het te bekijken., +31 314 623 306

Six young airmen are buried at the cemetery in Halle, a small village in the east of the Netherlands. Every year on 4th May, the Dutch Remembrance Day, a wreath is laid on each of their graves. The number of people who can remember how their bomber was shot down grows fewer by the year.

That is why Bennie Eenink decided to trace the story behind the six gravestones and the memorial.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bennie Eenink

(translated by Melanie Niesink)

The graves and the monument, probably 2006

1 September 1939

In the early hours of that Friday morning the German army invaded Poland. Within days it became clear that this war was going to be very different to any war other war there had ever been. Aircraft were no longer used for reconnaissance, as they had been during the First World War; they had become the prime weapon. Instead of endless battles in the streets of Warsaw, there was a three-day bombardment. By the time Poland surrendered on 28 September some 26,000 civilians had been killed in Warsaw alone.

The “New Dutch Water Defence Line”

The Netherlands anxiously observed the aerial war in Poland. It was evident that the Dutch defence was in no way capable of coping with attacks from the air. The underlying principle of the Dutch defence was that “Vesting Holland” [Fortress Holland] (The provinces of North and South Holland and the western part of the province of Utrecht) was to be defended to the bitter end. A vital role in this was to be played by the “New Dutch Water Defence Line”, the construction of which had begun back in 1815. It was a strip of land approximately 5km wide, between Muiden and what was then still the Zuiderzee (now the IJsselmeer Lake) which could be flooded under 40-60 cm water. Too deep for the infantry to advance but too shallow for normal vessels. The Water Defence Line was the final line of defence. If at all possible, the enemy had to be stopped before it reached that defence belt by such defence lines as the Grebbe line near Wageningen and the Peel-Raam position in the province of Brabant. And nearer the German border other, smaller measures were taken to delay the enemy advance. Describing the situation in his diary the late Mr B.D. Wisselink from the village of Halle-Heide wrote: "…….every serviceman has been called up, the bridges have been charged with explosives and guards have been posted. The same has been done to the local bridges, like the Vellevoortse Bridge to Ruurlo, the Bouwhuis Bridge to Doetinchem, the Poels Bridge to Westendorp and the Kieften Bridge to Varsseveld. They have also built a bunker next to the stream. On the road from Halle to Zelhem, just past Derk Overbeek, they have placed a tyre charged with explosives round the tree so they can create a road block…”

May 1940

In the first few days following the German invasion of the Netherlands it was evident that the Dutch defence was no match for the German aggression. The defence was heroic, on the hill at Grebbeberg, for example. During the clashes at Grebbeberg two inhabitants of Halle were killed, the 24 year old Eduard Peppelman and Derk Jan Heinen aged just 19. It was all to no avail. Just like Poland, the battle in the Netherlands was primarily an aerial conflict and was decided in the skies. On Tuesday 14 May 1940 Rotterdam was bombarded and more than 800 people were killed. Some 24,000 houses were destroyed, leaving 80,000 people homeless. The Netherlands surrendered.

|

|

|

| Eduard Peppelman | Derk Jan Heinen |

Britain

Bound by agreements, Britain and France were both drawn into the war following the invasion of Poland. However, Britain was initially extremely reserved about active involvement. The formidable fighting force the Germans displayed, particularly in the air, made the British cautious. They thought it best to improve their own air force first. The distance was also significant. It was impossible to fly over the Netherlands, still neutral at the time, so to reach Germany they would have to fly either over France of north of the West Frisian islands.

As the first air bombs were dropped on the Achterhoek on Tuesday night ….

The headline of an article in the Graafschapbode newspaper of Wednesday 29 May 1940. Once the Netherlands had surrendered the British were able to fly over the Netherlands, which reduced the air route to Germany considerably. This also entailed risks for our region, however, as the following excerpts of the article illustrate:

……..Monday night, following several successive nights when the incessant roaring of aircraft had unnerved the inhabitants of the Achterhoek1 and disturbed their sleep, a British bomber demonstrated, with an ostentatious display of force, how foolish and reckless it is to carry on regardless, believing that any precautionary measures against acts of war were in any way superfluous in the peaceful "Guelders Achterhoek". This has now been made painfully clear, evidence of which lies in the account of facts which occurred “somewhere in the Achterhoek” but which, for the usual reasons, we shall not publish ……….

The ‘Achterhoek’, literally meaning ‘back corner’ is a region in the eastern most part of the province of Gelderland, stretching to the German border

The British bombers would appear to have been off course when they dropped their bombs on the Achterhoek, or perhaps they were in dire straits, under German attack for instance. The whole article exudes pro-German sentiment and was probably severely censured or event written by the Germans. The British were naturally to blame for the bombing of the Achterhoek: ……., there is good reason to believe that these "random bombardments” presumably by British bombers flying off-course, will indeed become “systematic". In fact this trivial performance with fighter planes actually poses as great a threat if not far greater a threat to the people living in such unprotected areas than any other kind of war threat ….

The extensive article goes on to discuss the need for blackouts to make it harder for enemy planes to find targets:

…… People must ensure that all houses and buildings are appropriately blacked out every evening and night and remember, just two small tea lights on a ship led to the night-time bombing of the city of Emmerich, with all its disastrous consequences ……

The last sentence also suggests that the Germans had a finger in the pie as far as this article was concerned: …….. On Tuesday night The Achterhoek was taught a hard but valuable lesson, which will hopefully have instilled on the entire population that they must shake off any sloth and weaknesses from now on. Each and every person must recognise their duty in this respect, and their responsibility to themselves, their family and the community!!

Bombs on London and Berlin

On 24 August 1940 a German bomber flying over Britain went off course and dropped his bombs on a residential area as opposed to military targets. That residential area turned out to be a suburb of London. The damage was limited but the effect was massive. The British population was in shock; Prime Minister Winston Churchill assured the people that bombs would fall on Berlin within 24 hours. Indeed, in the night of 25 August 1940 some 50 British bombers were the first to reach Berlin. Here also the damage was limited but the psychological effect enormous. The fact that bombs had landed on Berlin enraged Hitler. Air Commander Goering had always ensured the Germans that “his” Luftwaffe would prevent that ever happening no matter what.

30 August 1940

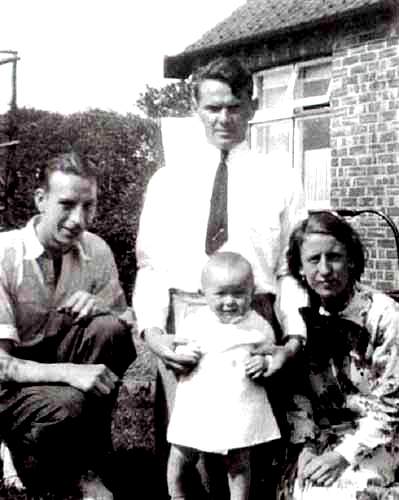

The British pilots returning from Berlin received a hero's welcome. Success whetted British appetites so bombers were sent back to Berlin again and again the following nights. And not just to Berlin, other targets including a number of airfields in Germany were bombed intensively. As was the case on Friday 30 August 1940. Not far from Newmarket lies the village of Stradishall where, in response to the German threat, an airbase had been built in 1937. That afternoon, several bomber aircraft at the base were made ready to fly to attack German airfields. One of those planes was a Wellington, tail number T2559. The crew consisted of pilot Lionel M. Craigie-Halkett (age unknown), co-pilot Wilfred B.S. Cunynghame (aged 22), the two wireless operators/air gunners Sydney J. Haldane (19) and Arthur B. Puzey (20), tail gunner George E. Merryweather (20) and the navigator/observer George H. Bainbridge (aged 29). Who were these young men? I wish I could tell you something about all of them but at this point in time I know very little about five of them. The only one I do have any information about is George Bainbridge. George was born on 25 February 1911. He joined the forces when he was young, originally serving with the Royal Navy. After a few years he was obliged to switch to the Royal Air Force when he turned out to be colour blind. This was apparently not a problem with the RAF; either that or he managed to conceal the fact. On 21 July 1936 he married Ethel Wright and on 30 May 1937 their son Brian was born. The young couple were not to enjoy their newfound parenthood for long; Ethel died three weeks after giving birth, aged just 26. It was not easy for George to combine the care for Brian with serving in the Air Force. A befriended couple, “Auntie Nell and Uncle Jack French” helped out and often took care of the little boy.

While bombs were being loaded into the Wellington T2559 the crew prepared for their mission, not knowing that this would be their last sortie. That evening at 20.48 hrs local time, they took to the skies. As evening fell, they flew over the British coast towards the Netherlands for the last time. The final entry written in the Operations Record Book read:”…after leaving base nothing has been heard or seen of the machine ……”

|

|

| Ethel Wright, the wife off George Bainbridge |

Brian and George Bainbridge with |

The drama above Halle

It is not exactly clear quite what happened above the Achterhoek. Various sources contradict each other. It is almost certain that the Wellington T2559 was not en route to Berlin, as was often said, but to a German airfield. However, it is not clear whether the bomber was on its outward flight or on the way back to Britain, still carrying the bombs. In that phase of the war aircraft often used to return still carrying the bombs because the bomb-release mechanism had failed or because they had not been able to locate their targets.

When the Germans spotted the British bombers they sent their own fighter planes in pursuit. It is not clear quite where these German planes came from. Most sources say it was Fliegerhorst (air-force base) Deelen near Arnhem. What is clear is that this resulted in air combat above the Achterhoek, as the Graafschapbode reported:

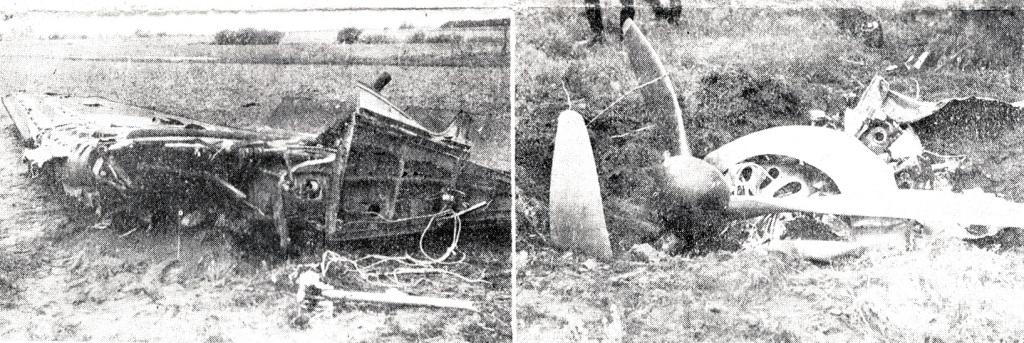

…….Friday night countless aircraft were operating above Eastern Gelderland and the skies were ablaze as their powerful searchlights scanned the heavens. The hostilities resulted in three British fighter planes crashing to the ground in flames killing, it is thought, 15 British airmen. The aircraft landed in "Kappenbulten" between the villages of Halle and Zelhem, in the fields on Veerweg in Giesbeek not far from the ferry across the IJssel, and one near Lobith……

What is known is that the gunners of a Wellington bomber managed to shoot down a German fighter plane. The German crew of two managed to parachute to safety before their plane crashed near the hamlet of Meddo near Winterswijk. It is possible that the gunners in the Wellington which landed in Halle were responsible for this. Bombs were also dropped during the dogfight.

The Graafschapbode: ….Several bombs landed in fields in Halle and Heelweg and the surrounding neighbourhood, including the Geurings farm in Heelweg, which suffered shell damage. Splinters went flying through three windows of the living room, breaking the light, among other things. At the neighbouring farm "de Horsterman" shell splinters killed a cow. Another bomb landed in a field in the vicinity near Jan Veldkamp's farm in Noorderbroek, while several other bombs landed elsewhere in the neighbourhood leaving craters in heath land, meadows and fields, albeit without causing too much damage ……

These bombs may have been dropped in an attempt to make the aircraft lighter and thus easier to escape. It is also possible that the bombs were released after the Wellington had exploded in mid-air, The Graafschapbode reported: …. The neighbouring farming population, awoken by the loud droning and several bombs exploding, suddenly saw a plane explode into flames high in the sky …

The Vickers Wellington T2559.

Mrs Anneke Wijkamp-Eenink (88 years old) recalls: ” I was living with my husband Derk, my mother-in-law and my brother-in-law Roelof at Heidendal farm, where the Dame family live today, at Aaltenseweg 21 in Halle. The house is about two hundred metres away from the spot where the plane crashed. It was around 11.30 p.m. and wed already gone to bed. Suddenly we heard a horrendous noise, the sound of planes, shooting, and the whole house lit up with the searchlights and tracer bullets. It was terribly frightening, we thought the whole house would be blown up. Looking back, that could well have happened because a large piece of a wing had landed in between our house and the neighbours house, which was only 20-30 metres away. It was obvious that something dreadful had happened behind the “de Kappe” farm. Once things had calmed down a little my husband and brother-in-law wanted to go out there. But they didn't get far. A lot of German soldiers were already on the site and they turned everyone away. Things remained unquiet for the rest of the night, perhaps the Germans thought some of the airmen had escaped and were hiding somewhere. It wasn't until daylight broke the next morning that it became clear that a drama had taken place here. That morning hoards of people came to look but the Germans kept them at a distance. Telling them that we lived there didn't help at all, we weren't even allowed onto our own land.”

Very early in the morning, however, it had apparently been possible to get close to the plane. In his diary Mr Wisselink (the smith known as the "Heidesmid") wrote: ”Early that morning I was one of the first to get to the scene behind the Kappe house, where the Germans were busy removing the body of an airman who was stuck in a piece of the aircraft, some sort of seat. When a couple of soldiers set about things a bit roughly a superior set them right saying “Er ist auch ein Soldat” (“He's a soldier too, you know”). They had to get a large sheet to carry him off in.”

Mrs Wijkamp: ”Later that morning my husband and a few neighbours were ordered to take the bodies to the mortuary in a horse-drawn cart”.

At the cemetery, on the Halle side, is a little building used, among other things, as a tool shed. There used to be a similar building on the Zelhem side of the cemetery as well, that was the mortuary. If there was no room at home, the deceased were laid there for people to pay their respects. The building later became redundant and was demolished.

The Graafschapbode reported: … The dreadfully mutilated bodies of the victims were taken to the mortuary at the general cemetery, laid on a bed of straw and covered …..

Mrs. Wijkamp: ” Over the next few days the Germans collected and removed the debris of the plane, although they had not found everything apparently. A few weeks later neighbour Leuverink, from the Kappe, found a wire sticking out of the ground. He started pulling and discovered there was a bomb attached, that had driven right into the ground. The Germans were called and eventually the whole neighbourhood was temporarily evacuated; we went to people living nearer Halle, and then they exploded the bomb”.

More debris was found elsewhere in the area, as another local newspaper, the ”Graafschapper” reported: ……It is a miracle there have not been more accidents, as the debris of the plane was scattered far and wide, and this area is fairly densely populated. Several bombs also landed in the woods, without causing any damage however.

The burial

The airmen were buried on Monday 3 September 1940 and the Graafschapbode printed the following account on Tuesday 4 September 1940: …… Just before three o'clock that afternoon many people, not just from Halle but from the broad vicinity, assembled there on God's acre, among whom we noticed the Right Honourable Mr. J. Rijpstra, burgomaster of Zelhem with his wife, as well as both local vicars, the Reverends Zijlstra and Troelstra. A division of the German armed forces under command of Hauptmann Hanssen presented guard of honour during the ceremony.

At exactly three o'clock the bodies, in simple black wooden coffins, were carried to the mass grave in the back right-hand corner of the cemetery, with German servicemen as bearers, while six wreaths were carried in the procession as it passed solemnly along the cemetery path. At the graveside a firing squad stood stiffly to attention under orders of a Feldwebel and while everything was ready for the ceremony to begin, a German airplane appeared out of thin air and flew over the churchyard in salute to the defeated foes, who had fought a heroic battle and lost. Then Hauptmann Hanssen stepped forward and gave a military salute as each coffin was lowered, and when all six coffins had been placed side by side in the large, deep grave he requested one minute's silence as a silent tribute to the fallen ones. Hauptmann Hanssen then rendered a moving speech, in which he expressed that we should not consider these fallen men as the defeated enemy but also as soldiers who had fought bravely for their Country. Perhaps these fallen warriors too have parents, wives and children, brothers and sisters and fiancées – the speaker said - and it is only natural and our obligation as soldiers, that we bury these fallen fighters here, in foreign soil and far from home. The speaker made reference to the heroic death of these soldiers who had rendered the ultimate sacrifice. Then three almighty salvos sounded from forty guns as a final salute.

Rev. Troelstra, the Dutch Reformed pastor of Halle, stepped forward and, speaking in the German language, said touching words taken from the Holy Bible "Bei den Herrn ist die Gnade" (“There is mercy with the Lord”). The ceremony was concluded by the saying of the Lord's Prayer.

Burials with military honours were not uncommon in this phase of the war. Human motives might have contributed to this but propaganda undoubtedly played a part as well. The Germans wanted to demonstrate their best intentions towards the Dutch. That same afternoon in Giesbeek British airmen were buried who had also been shot down in the night of 30 August. Again with military honours but without an airplane this time. Later on in the war increasingly less attention was paid to enemy burials.

The monument

The Graafschapbode also mentioned:

…..When the graves were covered, a large wooden cross painted black was placed on top of the grave, with the words: “Hier rusten 6 Engelsche vliegers, gevallen in den nacht van 30-31 Aug.1940….” (” Here rest 6 British airmen, who died in the night of 30 August 1940....”)

It is not known who designed the cross; we do know that it was made by Middeldorp, a builder in Zelhem. It apparently met with German approval because a good year later, in July 1941, the Wehrmachtkommandantur in Arnhem sent a letter to the municipal authorities about the cross in Halle. It seems inspection by the Germans had revealed that in many municipalities with allied war graves there was either no cross at all or the cross was of inferior quality. The municipal authorities were ordered to erect a “Halle” model cross and to inform the Wehrmachtkommandantur accordingly. A photograph of the cross in Halle had been enclosed with the letter as an example.

After the war, six headstones were erected on the grave, the same ones as those erected on British war graves worldwide. The headstones were probably erected in 1954. This can be deduced from letters exchanged between the burgomaster of Zelhem and the Imperial War Graves Commission in Brussels. In April 1954 the burgomaster complained that: … several people have been working on the graves in Halle, removing the existing memorials to replace them with new stones. The work had to be stopped because of the frost and now everything is still lying there like a wilderness.….

It emerged that one of the six stones had been damaged during transport and that this was the cause of the delay.

Particularly noteworthy is the fact that a memorial was erected behind the headstones. Describing the cemetery in Halle in various books and on their internet site the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) says: They have the usual Commission headstones, and in the centre is a memorial to these airmen which was erected by the local people. In Britain they also know that the monument was unveiled on 31 August 1945 by the British Captain White, who was commander in Zutphen at the time. It is also said that the weather was so bad that the photographer who attended the ceremony was unable to take any photographs. It is possible that the photograph of the memorial printed with this article was taken very shortly after the unveiling ceremony. Looking at an enlargement of the photo, it is clear that the ground is sodden and the memorial still wet from the rain. The enlargement also shows the ribbon on the floral tribute, with the words: “De burgerij van Halle” (the citizens of Halle). It is not clear whether there was anything else. Behind the memorial is a German grave, recognisable by the German helmet. This can but lead to the conclusion that the photo could not have been taken any later than 1948 as the graves of the five unknown German soldiers were moved to the German War Cemetery in Ysselsteyn (Limburg, NL) in January 1949.

4 May 2005

It's around quarter to eight in the evening and another beautiful spring day draws to an end. As the church bells start to ring out over Halle, a procession of forty, maybe fifty people sets off from the Grote Kerk (Main Church) towards the cemetery. Leading the procession is a delegation of the community interest group "Halle's Belang", carrying a wreath. A wreath which was about to be laid in front of the six graves of the fallen airmen. I am part of that procession, walking somewhere at the back. As we near the cemetery we turn a corner, which enables me to get a better look at the other people in the procession. The average age is high, I conclude. Save a few schoolchildren participating in the remembrance ceremony, there are hardly any younger people. A little later, standing near the graves, I wonder how many of the people present had actually witnessed this tragedy. All I know myself is that they crashed near the Kappe” farm on Aaltenseweg. And what about the family in England? Have any surviving members of their families ever visited these graves? And what will it be like in ten, fifteen years time? Will the Halle community still be interested in Remembrance? Or will the representatives of "Halle's Belang" laying their wreath be the only ones there? After the ceremony, encouraged by the good weather, several people lingered in the car park chatting. It seemed I was not the only one wondering about that. By the time we parted company I had more or less resolved to examine the possibilities of recording this piece of Halle history and trying to contact the surviving relatives in Britain.

You've got to start somewhere, so I decided to visit the AVOG's Crash Museum in Lievelde. The Achterhoek Aircraft Wreckage Excavation Group (Achterhoekse Vliegtuigwrak Opgravers Groep =AVOG) was founded in 1972. Besides hoping to help shorten the list of people "missing in action", the AVOG especially aims to preserve part of local history for future generations. Since 1972 the foundation has been charting the events of the aerial war above the Achterhoek region of the Netherlands during the period 1940-1945. Thais research led to the creation of a museum in Lievelde, which was opened in 1981. As well as being a tribute to the allied airmen who sacrificed their lives for our freedom, the museum is a permanent exhibition of the technical aspects of the aerial combat.

In the museum, to my amazement, I saw a newspaper with a report of the crash and a photograph of one of the airmen, George Bainbridge. When I explained my interest, I was told that a British couple, Brian Bainbridge and his wife, had visited the museum in April 1990. It emerged that Brian was a son of George Bainbridge, one of the airmen killed in Halle. Brian had given AVOG the photograph of his father. Brian and his wife had also visited his father's grave in Halle. The museum had kept the family's address and I decided to send them a letter. Unfortunately Brian had died several years earlier. His widow, Mrs Ann Bainbridge told me: “My husband Brian was just a few weeks old when his mother died. His father George couldn't care for him all the time because of his work with the Air Force. Friends of my father-in-law helped him. When George was killed in the crash in Halle my husband was sent to his grandparents and he grew up there. His grandparents never told him much about his father and mother. It might have been their way of protecting him from grief. It wasn't actually until after his grandparents had died that he started to search for more information about his parents. That is what eventually brought us to Halle and the surrounding area in the spring of 1990. We visited Halle again a few years later”.

During my quest, I placed an announcement in a local newspaper, to which I received considerable response. I learned, for example, that the fiancée of one of the airmen had visited Halle in or around 1948. And the father of Arthur Puzey had apparently attended the Remembrance service in Halle in 1947. The ceremony is said to have been held in the public house "Zaal Nijhof" (the bombed church had not yet been rebuilt) and Puzey senior apparently said a few words. He was also with the Royal Air Force and the archives refer to him as Squadron Leader George Arthur Puzey. A Squadron Leader also often used to fly and would have been responsible for a group of between twenty and thirty bombers.

I received a remarkable reaction from a Mr Johan Heinen (84), now living in Doetinchem but who had been born at Veengoot 5 in the village of Halle-Heide.

Mr Heinen: ”At the time I was working as a farmhand at Waarlo in Meene. My brother had been killed a few months earlier at Grebbeberg and that spurred me to join the resistance. Our commander Mr Stomphorst, who was schoolmaster at the Meene school, came to me that morning to ask me to size up the situation at the Kappe and gather as much information as I could about the type and tail number of the aircraft.

And it was of course important to know whether the airmen had escaped or been killed. The Germans kept onlookers at bay but I did manage to talk to a German sentry for a while. He and I also went a bit closer and it really was a dreadful sight, I don't want to go into any more detail.

Near the scene I found a piece of a glass canopy and some kind of leather helmet that had belonged to one of the pilots. I wore that flying helmet for years when riding my motor bike until crash helmets were made obligatory. Years later it unfortunately got lost when we were moving house. It was a wonderful helmet, with holes for the headphones. In fact it was such a fine example that during a routine police check I was once asked where I had found it ….

Mr Bert Schieven from Zelhem is an avid collector of war memorabilia. His collection includes a flying helmet which came from the Halle Wellington. His father, a boy at the time, had found it with a friend near the plane.

The late Mr Louis Duitshof (Meuhoek) found a photograph near the wreckage of the plane. It showed a group of servicemen near a plane, some of them with kit. It was obvious that the photograph had come from the aircraft but it was not clear whether the airmen in the plane were actually the men in the photo. I received a photograph via Mrs Bainbridge that closely resembled the one found in Halle. Both photos can be seen with this article. It is evident that the two photos were taken in the same place, one after the other. The Bainbridge family is not sure either whether this is the crew of the plane that crashed in Halle. According to Mrs Bainbridge her father-in-law George Bainbridge is in the top row, third from the left. That is second from the left in the Halle photo. It seems plausible that the five men in the front are mechanics, responsible for servicing the aircraft and loading the bombs. The back row in the English photo and the six in the Halle photo are therefore the crew. The two men in uniform are the pilots, as can be seen by the double wings on their uniform. Nothing more is known at this point in time. Mr Duitshof is said to have been extremely proud of this photo which was given place of honour in his living room for many years.

Photo from Mr Duitshof.

Photo from Mrs Bainbridge

I naturally sought more information about the memorial but, strangely enough, very little has emerged. Until now, nobody in Halle has been able to tell me anything about the realisation and/or unveiling of it. Neither has anything been found in the archives, not in the "Halle's Belang" archive or any other archive. Two archivists at the Regional Archive (Streekarchief ) in Doetinchem were so kind as to help me delve into the archives of the Reformed Parish (Hervormde Gemeente) Halle, the Reformed Church (Gereformeerde Kerk) Halle, and the civil municipality of Zelhem. We also worked our way through numerous Graafschapbode newspapers of the time. The result of a whole evening's work was minimal; a single, yet remarkable letter. In September 1946 the father of one of the deceased airmen asked the burgomaster of Zelhem for a photograph of the grave and memorial. In his reply the burgomaster explained that this was not then possible as the names on the memorial were incorrect. Indeed, if we look closely at the aforementioned photograph with the German grave in the background, the names clearly include several spelling mistakes. The photograph also shows that the names had been carved into the stone. Anyone looking at the memorial today will see that a metal plaque, with the names spelled correctly but in a different order, has been screwed onto the stone. Perhaps the first, incorrect names remain concealed behind the plaque.

Finally

Since 4 May 2005 I have been absorbed by the Second World War. I have worked my way through piles of books, spent many an evening surfing the Internet, and visited countless war museums and war cemeteries, from Grebbeberg to Reichswald in Germany. In former East Berlin I stood on the spot where, beneath me, the remains of Hitler‟s bunker can be found. And en route to Berlin, sitting comfortably in a Boeing 737, I tried to imagine how it would feel to be flying towards Berlin in a Wellington bomber, with only canvas for protection and carrying a highly explosive cargo of bombs across blacked-out enemy country knowing that you could be attacked at any moment.

I have also come into contact with many, many people. People in Halle and the wide surrounding area, and surviving relatives in England. I am so very grateful to all these people who were willing to share their stories and emotions with me. If I sum up all their experiences I can only agree with what so many people have said before me: one evening, just a few hours a year, to stop and remember what happened, to commemorate those who made the ultimate sacrifice so that we can live our lives in freedom, that has to be the very least we can do. In honour of the fallen, and as a token of gratitude to their families both here in Halle and in Britain. I hope that this article may contribute to the continuation of Remembrance in Halle. A commemoration in particular of “our” Halle boys Eduard Peppelman and Derk Jan Heinen and “our” British airmen.